The

settlement is made up of three parts:

1.

A small building with quadrangular

plan delimited by dry stone walls;

2.

Two short standing stones, 44

cm apart, placed in front of the south wall of the building;

3.

A standing stone with a natural

hole in its top end vertically fitted in a natural fissure of the ground, about

30 meters away from the building and the other two standing stones.

Natural

Environment and Archaeological Framework

The settlement is

located in an area part of the relic of an old calcareous periplain

(i.e. a low-relief plain which is the final stage of a fluvial erosion,

occurred during times of extended tectonic stability), formed during the

Miocene. Here, the weathering excavated three rivers (i.e. Pora,

Aquila and Sciusa) and an intricate system of underground

waters that created over 400 grottos. Archaeological investigations carried out

in the past decades highlighted use of some of these grottos by the mankind,

since the Lower Palaeolithic. Some of these grottos are located in short

distance from the observatory. These are:

1.

The Grotta

degli Zerbi (Zerbi’s grotto), where some archaeological evidences and

fossil fauna were excavated and dated to the Mousterian;

2.

The Riparo

Fascette I (Maggi, Pastorino,

1984, pp. 171–175) where archaeological evidences

dated to the Copper Age (phase of the Middle Ligurian

Neolithic called del Vaso a Bocca

Quadrata, VBQ, or of the pot with squared mouth) were

excavated;

3.

The Grotta

1 del Vacché (Odetti,

1987a, pp. 129–131), with archaeological evidences dated to the Copper Age;

4.

The Refuge of Bric Reseghe, that was used as a

storage area throughout all the chronologic phase of the VBQ (Odetti, 1987b, p. 132);

5.

The Castellaro

di S. Bernardino: a prehistoric settlement on the top of the St. Bernardino

hill that can be dated to the Bronze Age (Del Lucchese,

1987, pp. 133–135 and personal communication of

the same author with one of the authors of this study).

Large

concentrations of petroglyphs are located in areas such as Ciappo de Cunche, Ciappo dei Ceci (also

known as Le Conchette;

Priuli, Pucci, 1994, pp. 35–43) and at Mount

Cucco (Codebò, 1996, pp. 138–141). Unfortunately, none of these petroglyphs can be dated

accurately since there are no comparison of known age in the area for such type

of rock art (Issel, 1908,

pp. 467–484; Giuggiola, 1973, pp. 111–167; Tizzoni, 1976, pp. 84–102; Leale Anfossi, 1976, p. 18–27; Studi Genuensi, 1982, pp. 1–84; Odetti,

Ravaccia 1988, pp. 13–15.; Fella, Zennaro,

1991, pp. 247–248; Priuli, Pucci,

1994, pp. 35–55; Codebo’, 1996, pp. 138–141; Codebo’, 1999).

At the north and south ends of

the mountain ridge are located two Romanesque churches: St. Lorenzino

and St. Cipriano. The latter was in connection with

the medieval settlement of Lacremà, currently

abandoned. After detailed studies, the church of St. Cipriano

revealed an early Christian apse (Frondoni, 1990, pp.

423–426) that was probably an influential point of the Julia Augusta. This was

an important Roman road built by the Emperor Augustus since the 13 B.C. to

connect Rome with the southern Gaul. Important remains of this road are the

five bridges in the Ponci’s

Valley, in very good conditions still now (although they were re-built at the

time of Emperor Adrian).

From an archaeoastronomical point of view, the same ridge hosts

some important evidences such as:

1.

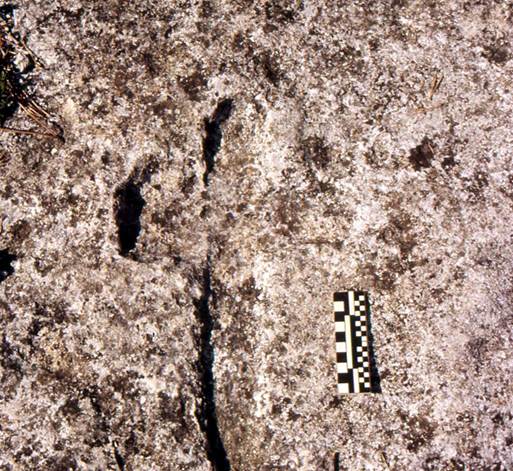

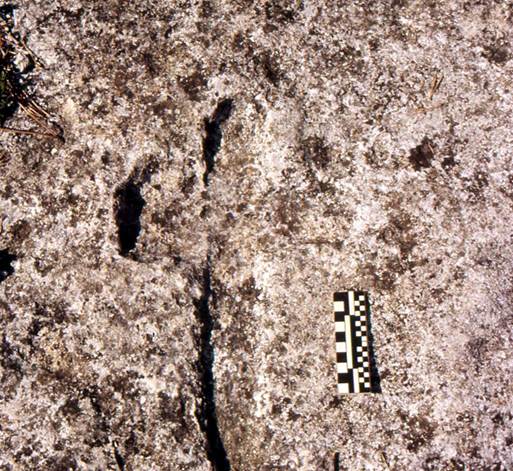

Some cruciform petroglyphs at Ciappo de Cunche (fig. 1) and at Ciappo dei Ceci

(fig. 2), oriented according to the main cardinal points (Codebò,

1997a, pp. 735-751);

2.

The Pietra

di Marcello Dalbuono (the Marcello Dalbuono’s stone), showing two solar orientations: toward

the equinoctial sunset and the summer solstice sunset (Codebò,

1999);

3.

The Camporotondo’s

cromlech (Codebò, 1997a, pp

735-751), currently under investigation by two of the authors of this paper.

The cromlech shows three corners interrupting a circular profile. Two of the

corners are oriented toward the cardinal points north and south, respectively.

Figure

1. Cruciform petroglyphs at Ciappo de Cunche (copyright Mario Codebò).

Figure 2. Cruciform petroglyphs at Ciappo dei Ceci (copyright Mario Codebò).

Archaeological

Evidence at Bric Pinarella

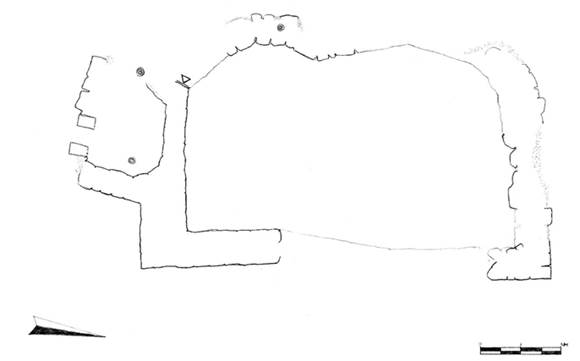

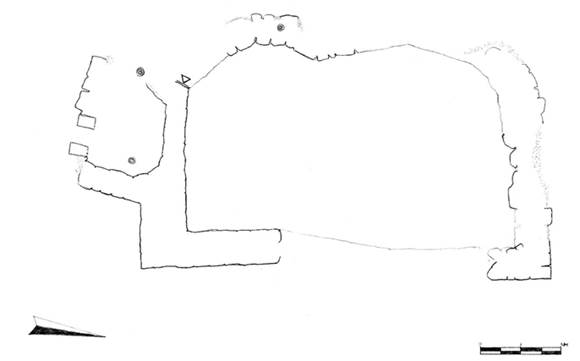

The building at Bric Pinarella is the largest

evidence of the settlement. Currently, its structure can be described as a

ruined hut related to a type of buildings locally called caselle (plural; casella

singular). The building has a rectangular plan about 10 m long and 6 m wide

(fig. 3). Wall’s orientation is as follow:

East wall: 346°↔171°;

West wall: 346°↔173°;

North wall: 243°↔61°;

South wall: 235°↔78°.

Figure 3. Plan of the building at Bric

Pinarella. Black dots near the south and west walls

provide the position of the trees. The single line in the east wall is used to

suggest the inner alignment (the wall was covered by debris at the time of the

survey; survey G. Pesce)

Thickness of the

north and east walls measured on their top is of about 0.85 m, whereas the

south wall is about 1.10 m thick (thickness of the west wall at the time of the

survey could not be measured precisely because of some debris covering its

central part). Space available inside the building is about 8 m long and 4 m

wide.

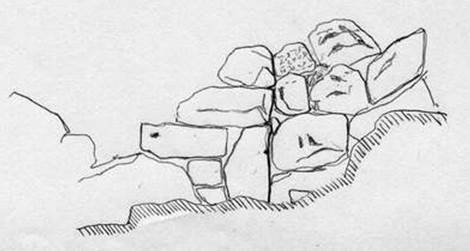

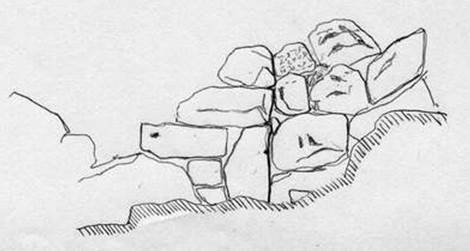

No openings such

as doors or windows are currently visible in these remains. However three

vertically aligned stones in the inner front of the south wall suggest

existence of an interruption in the fabric of the wall (fig. 4) that could be

related to an opening (such as a door) or a corner of an earlier layout of the

building (which, in this case, could have had at least two building phases).

Figure 4. Sketch of the elevation representing the interruption in the fabric

of the south wall that could be related to an opening (such as a door) or a

corner of an earlier layout of the building.

Walls are

preserved for up to 2 m above the ground and are made of stones of various

sizes, laid without mortar (fig. 5). Stones were sourced locally and used

without specific preparation. Stone alignments within the walls are irregular

and characterized by a high number of voids. Cornerstones are generally bigger

than the other stones. Overall, the building technique can be described as

inaccurate and attributed to non-specialized builders.

Figure 5. East wall of the "casella"

built without the use of mortar (copyright Mario Codebò).

The south space

outside the casella

is occupied by two walls about 65 cm thick, built almost perpendicularly to the

south wall of the main structure. All together, these walls surround an area of

1.85 x 2.42 m, which is adjacent to the main compartment of the building but

inaccessible from it. The only access to this small space was probably located

in the south side, currently partially destroyed. The only existing remains on

this side of the construction are two short standing stones 0.44 metres apart

that stand out from the rest of the walls (fig. 6).

Figure 6. The

two standing stone located near the southern wall of the building in figure 3.

The stones are 44 cm apart (copyright Alfredo Pirondini).

The space between

these stones is too small for being crossed by an adult human being.

Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that the small compartment outside the

main building was functional to the activities taking place in the adjacent

structure.

With the goal of

dating the building, the area inside the main compartment close to the east

wall (where archaeologists supposed that some archaeological evidence could

have been found), was archaeologically investigated by Angiolo

Del Lucchese (archaeologist and director of the Soprintendenza Archeologia della Liguria) together with the archaeological practice

"G. Viarengo". Unfortunately, the

excavation did not produce evidence of anthropic origin so that, to date, no

chronological information is yet available on the use or on the construction

time of this structure. Difficulties in investigating the archaeological

context in the whole area of Finale Ligure are very

common. This is due to the karstic nature of the soil and to the erosive action

of the rain that, except for the grottos, easily washes away and mixes the soil

and, with it, the archaeological and geological record. An example of this

effect (called debitage

by French archaeologists) is the record found during the archaeological

excavation of the site of St. Antonino of Perti carried out by Prof Giovanni Murialdo

and dated to the Late Antiquity. In this site, archaeological evidences from

the Mousterian Age (Middle Palaeolithic) were found mixed with materials from

the Bronze Age and with materials from Byzantine Age, in a single stratum of

few centimetres thickness.

About 30 m

southeast from the casella

is located a large rocky outcrop characterized by a fracture some centimetres

wide and several centimetres deep, cutting through the hole outcrop. This is at

the edge of a steep slope facing east toward the upland plain of the Mànie. The fracture hosts an isolated standing stone with a

hole in its top end (fig. 7). According to the former curator of the Civic

Archaeological Museum of Finale, Mr Giuseppe Vicino,

who surveyed the site several times, the fissure, the standing stone and the

related hole are of natural origin and acquired their characteristics because

of the chemical and geological composition of the stone, called Pietra del Finale. Geologist Dr Davide Gori, who inspected some

photographs of the outcrop, confirmed the natural origin of the fissure.

Figure 7. Standing stone vertically fitted in a natural

fissure of the rock with a natural hole in its top end. This stone is about 30

meters away from the building in figure 3 (copyright Mario Codebò).

However, despite

the natural origin of the three elements, arrangement of the standing stone in

the fissure and placement of the hole at its free end cannot be considered

natural. This is confirmed by the presence of a stone fragment at the bottom of

the standing stone, used to fix it in the fracture. Presence of this fragment

suggests that insertion of the standing stone in the rock is, actually, of

anthropic origin.

Astronomical

Functions

First person to

point out an astronomical alignment of the standing stone overlooking the

upland plane of the Mànie was Mr Pino

Piccardo, an associate of the Civic Archaeological

Museum of Finale Ligure (Mr

Giuseppe Vicino, personal communication with one of

the authors of this paper). Mr Piccardo found that the

hole in the standing stone, frames the point where the Sun rises during the

equinoxes. To confirm this observation and verify further astronomical functions

for the whole site, Mario Codebò carried out a full archaeoastronomical survey from 21st to 23rd

March 2003.

Measurements

taken with a prismatic compass Wilkie of the

horizontal arch visible through the hole when the compass sight is placed

against the hole (e.g. fig. 8) is 74° – 93°.

Figure 8. The sunrise on

23rd March 2003, photographed with the camera’s lens against the

hole (copyright Mario Codebò).

This implies that

the sunrise can be seen from approximately mid-March to mid-April and from mid-September

to mid-October. However, observation of the same horizontal arch from short

distance (i.e. with the compass sight not against the hole) allows seeing the

sunrise only at the equinoxes. In such conditions, the Sun looks like a point

of light as represented in figure 9.

Figure

9. The point of light created by the sun

when observed through the hole from some distance from the stone and at the

equinoxes’ sunrises (copyright Sara Pelazza).

All astronomical

functions identified within the site during this study are listed below:

The

hole in the standing stone allows identification of the sunrise at the

equinoxes on the skyline of the Mànie upland.

1.

The sunrise during the rest of

the year (i.e. between two solstices) is clearly visible on the Manie’s horizon from the location of the standing stone

(although outside the hole). The hole in the standing stone allows

identification of the elongation of the Sun from the east cardinal point.

2.

The two standing stones in

front of the south wall of the casella allow

identification of:

a.

The Sun’s upper

meridian transit and, therefore, the moment of the true noon (fig. 10).

Figure 10. Shadow of the gnomon when it is positioned in

between the two standing stones represented in figure 7. At the time in which

this image was taken, the time of the local (or true, or astronomical) noon was

12:33:22 on 23rd March 2003 (local const.: 12:26:40; equation of

true time on 23rd March 2003: +06:42; copyright M. Codebò).

b.

The different

altitudes of the Sun during its meridian transit, through the four seasons. By

correlating the various altitudes of the Sun with the elongations of the two points of sunrise between the two solstices,

it would have been possible to identify the width of the diurnal arc of the

Sun. This arch is minimum during the winter solstice (when the Sun’s meridian

altitude is at its minimum and the rising point is the southern) and is maximum

during the summer solstice (when the Sun’s meridian altitude is at its maximum

and the rising point is the northern). At the equinoxes, when the Sun rises

within the hole of the standing stone, the related meridian altitude is

intermediate. Theoretically, it would have been possible to measure also the

obliquity of the ecliptic, if precise tools for Zenith measurement were

available.

c.

The Moon’s upper

meridian transit.

d.

The daily delay of

about 50 minutes of the Moon transit over the local meridian, compared to any

star.

e.

The difference between

the sidereal month (27.32 days) and the synodic month (29.5 days).

Conclusions

This study

demonstrates the uniqueness of the remains at Bric Pinarella. This observatory is located in an area (called Finalese) that

has been populated since the Lower Palaeolithic and therefore has accumulated a

rich archaeological record. The few but distinctive remains still visible on

site do not allow dating the settlement but provide unequivocal evidence of the

interest and of the tools used in the past to study the movement of celestial

bodies.

In fact, although

the age of the archaeological evidences at Bric Pinarella is still unknown, it is possible to suppose that

the site was used as a rudimentary astronomical observatory: a kind of

elementary Greenwich astronomical observatory along the northern coast of the

Mediterranean Sea.

We hope that

these findings will foster new archaeological investigations in particular

aimed to date this ancient site that possesses characteristics to some extent

unique (at least in Italy) since it allowed the simultaneous measurement of the

most important astronomical times: the daily ephemerides.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to

everyone who contributed to this research and, in particular to: Davide Gori; Angiolo

Del Lucchese; Tiziano Mannoni; Pino Piccardo;

Giorgio Viarengo; Giuseppe Vicino.

Thanks are also due to Mr. Lorenzo Carlini, Ms. Sara Pelazza and Mr. Alfredo Pirondini

for having granted the right to publish their photos.

Notes

According to the

requirements of the Italian Universities, we declare that, although this paper

is the product of a collaborative work, "Introduction" and the

section "Natural environment and archaeological framework" were

written by H. De Santis; section "Archaeological

evidences" was written together by H. De Santis

and G.L. Pesce; section "Astronomical

functions" was written by M. Codebò.

References

·

Codebò, 1996 – Codebò, M. Segnalazioni inedite

sul Monte Cucco nel Finalese. In: Bollettino

del Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici, 29, Edizioni del Centro, Brescia, Italy, 1996, pp. 138–141, http://www.archaeoastronomy.it/segnalazioni_inedite_monte_cucco.htm.

·

Codebò, 1997a – Codebò, M. Prime indagini archeoastronomiche

in Liguria. Memorie S.A.It., 1997, 68(3), Italy, pp. 735-751,

http://www.archaeoastronomy.it/prime_indagini_archeoastronomiche.htm.

·

Codebò, 1997b – Codebò, M. Problemi generali dell'indagine archeoastronomica. In Atti del I Seminario A.L.S.S.A., 1997, Genova, Italy, http://www.archaeoastronomy.it/corso_elementare_archeoastronomia.htm.

·

Codebò, 1999. – Codebò, M. Archaeoastronomical

hypotheses on some Ligurian engravings. In: I.F.R.A.O. Proceedings of the World Congress

of Rock Art News95, Centro Studi e Museo d'Arte Preistorica

Ce.S.M.A.P., Pinerolo (TO),

Italy, 1999, CD–Rom, http://www.archaeoastronomy.it/archaeoastronomical_ipoteses.htm.

·

Codebò, 2010

– Codebò, M. L'algoritmo giuliano del Sole. In Atti del XII Seminario A.L.S.S.A.,

Genova, Italy,, http://www.archaeoastronomy.it/algoritmo_sole.htm

.

·

Codebò, 2013 – Codebò, M. Il metodo

nautico. In Atti del XV Seminario

A.L.S.S.A., Genova, Italy, http://www.archaeoastronomy.it/Metodo_nautico.htm

.

·

Codebò, 2015 – Codebò, M. Dall'altezza

misurata all'altezza vera. In Atti del

XVI Seminario A.L.S.S.A., Genova, Italy, http://www.archaeoastronomy.it/altezza_misurata_vera.htm

.

·

Codebò, De Santis, Pesce, 2011 – Codebò,

M.; De Santis, H.; Pesce, G.L. L'osservatorio in pietra di Bric Pianarella

(SV). In Astronomia culturale in Italia,

edited by Società Italiana di Archeoastronomia, Milano, Italy, 2011, pp.

177–185, http://www.archaeoastronomy.it/BricPianarella.htm

.

·

Del Lucchese, 1987 – Del Lucchese, A.

Bric Reseghe. In Archeologia in Liguria

III.1: Scavi e Scoperte 1982–1986, Tormena, Genova, Italy, 1987, pp.

133–135.

·

Fella, Zennaro, 1991 – Fella, M.;

Zennaro, D. Petroglifi inediti al Riparo dei Buoi. In Atti del Convegno su M.

Bégo, Tende, France, 1991, pp. 247–248.

·

Frondoni, 1990 – Frondoni, A.; S.

Cipriano, Campagna di scavo 1986. In Archeologia in Liguria III.2: Scavi e

Scoperte 1982–1986, Tormena, Genova, Italy, 1990, pp. 423–426.

·

Giuggiola, 1973 – Giuggiola, O. Le

incisioni schematiche dell'Arma della Moretta. In: Rivista di Studi Liguri,

XXXIX, Bordighera, Italy, 1973, pp. 111–167.

·

Issel, 1908 – Issel, A. Liguria

preistorica. In Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria, XL, Genova, Italy,

1908, pp. 467–484.

·

Leale Anfossi, 1976 – Leale Anfossi, M.; Il Ciappo del Sale.

In Mondo Archeologico, 9, Firenze, Italy, 1976, pp. 18–27.

·

Maggi, Pastorino, 1984 – Maggi, R.; Pastorino,

M.V. Riparo Fascette I. In Archeologia in

Liguria II: Scavi e Scoperte 1976–1981, Tormena, Genova, Italy, 1984, pp.

171–175.

·

Odetti, 1987a – Odetti G.; Grotta I del

Vacché. In Archeologia in Liguria III.1:

Scavi e Scoperte 1982–1986, Tormena, Genova, Italy, 1987, pp. 129–131.

·

Odetti, 1987b – Odetti, G.; Riparo del

Bric Reseghe. In Archeologia in Liguria

III.1: Scavi e Scoperte 1982–1986, Tormena, Genova, Italy, 1987, p. 132.

·

Odetti, Ravaccia, 1988 – Odetti, G.;

Ravaccia, C.; Aggiornamento sulle incisioni del Finale. In: Atti del II

Convegno sulle Incisioni Rupestri in Liguria, Millesimo (SV), Italy, 1988, pp.

13–15.

·

Priuli, Pucci, 1994 – Priuli, A.; Pucci,

I. Incisioni rupestri e megalitismo in

Liguria. Priuli & Verlucca, Ivrea (TO), Italy, 1994.

·

Studi Genuensi, 1982 – Atti del convegno

sulle incisioni rupestri in Liguria. In: Studi Genuensi, NS, Genova, Italy,

1982, pp. 1–84.

·

Tizzoni, 1976 – Tizzoni, M. Incisioni

all'aperto nel Finalese. In: BCSP, 13–14, Capo di Ponte (BS), Italy, 1976, pp.

84–102.

© This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Torna all’indice cronologico.

Torna all’indice tematico.

Torna

alla pagina iniziale.