ARCHEOASTRONOMIA LIGUSTICA

Articolo in corso di stampa sugli atti del Congresso internazionale “Représentations d’astres, d’amas stellaires et de constellations dans la préhistoire et dans l’antiquité” tenutosi presso il Musée Départemental des Merveilles, in Tenda (F) dal 24 al 27 settembre 2012.

Archaeoastronomical

hypothesis about the “Capitello dei Due Pini”, Val Camonica, Italy

Mario Codebò, Henry

De Santis

Résumé

Une étude pluriannuel d’archéoastronomie a démontré que le Gravure Camun

du Soleil, dans le Capitello

des Deux Pins, en localité Plas (Val Camonica, Italie), peut

être interprété comme une représentation stylisée

de l'excursion annuelle du Soleil

le long de le profile ouest de l’horizon visible - le coucher du

Soleil aux équinoxes et des solstices - et le mouvement

apparent de

Riassunto

Uno

studio archeoastronomico pluriennale ha dimostrato

che il petroglifo camuno del Sole, presso il Capitello dei Due Pin in località Plas (Val Camonica, Italia)i, può essere interpretato come

una rappresentazione stilizzata dell'escursione annua del Sole sul profilo

occidentale dell'orizzonte visibile - i tramonti agli equinozi ed ai solstizi -

e del movimento apparente lunare intorno all'astro diurno. Si è anche

constatato che gli ultimi raggi del Sole al tramonto durante il solstizio

estivo illuminano la sola parte superiore del Capitello dei Due Pini, ove è

rappresentato il disco solare. Gli autori ritengono che ciò, unitamente ad

altri elementi, confermi l’interpretazione, già proposta da altri in

precedenza, della località Plas come antico luogo di

culto del Sole.

The research

An

archaeoastronomical research focused on Camunian site

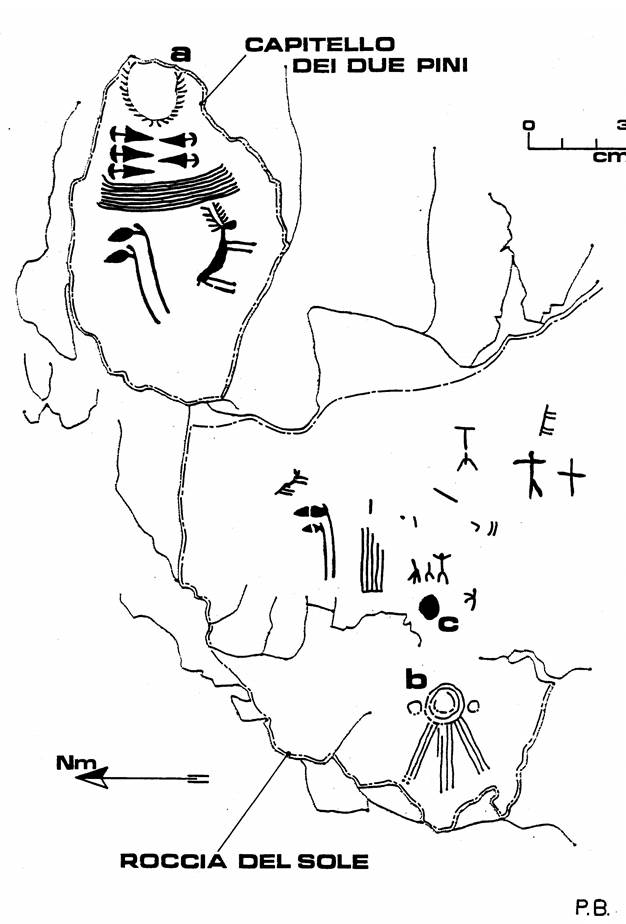

Plas, marked by very beautiful engravings (picture 1),

was proposed for the first time by Elena Gervasoni in

1997. At that time, she invited

|

Picture 1: The

engravings of Plas (drawing by |

While the 1997

survey ended with a first contact on the environment and with measuring about

two churches’ orientation, Codebò thought to find in the site Plas the typical characterizations of prehistoric cult,

basing on similar experiences (Codebò and Michelini,

1997a, pp. 341-358; Codebò, 1999). The characterizations are: rise on

surrounding ground, panoramic view, heathen frequentation, and Christianization

marks.

After studying the

site’s geomorphology, with a steep left mountainside, and after considering the

tradition of a sacred wedding between the male principle of Pizzo

Badile Camuno and the

female principle of Concarena, we thought Concarena were the focus of ancient observations (tradition

of the wedding is reported by Fratti and Gervasoni; meteorological observations reported in Priuli, 1983, picture n. 1 and Brunod

1997, picture n. 23; astronomical observations reported in Beretta, 1997,

pag.68).

After that, Barale and Codebò found a similar mountain hierogamy in the

We observed that

behind Concarena’s outline we can watch the whole

journey of sunset during the year and, given the fact that two engravings show

the Sun, we concluded that it was the same Sun the object of the cult.

Moreover,

Calzolari, Codebò, Fratti and Gervasoni

were already able to observe, during September 1997, the evening projection of

light and shadows behind the Concarena. This vision

could have been intended as an epiphany of the mountain Gods, like the one that

it is possible to observe sometime behind the

|

Picture 2: The

Sun’s (Camunian) Engraving (photo by |

Picture 3: The

Sun’s (Camunian) Engraving (drawing by |

The further step

wanted us to verify our hypothesis and understand the reason for the three Sun

rings, instead of one. So we began to observe and take pictures of the Sun

during three key moments: equinox and solstices. This process went through

winter solstice in 1997- summer solstice 1999. We used the following tools: graduated

spherical surveyor’s cross with direct reading of

Furthermore we

realized that on equinoxes (data of

|

Picture 4: The

equinoctial sunset (photo by |

With the height

above the skyline of 7°, the astronomical azimuth is 264° nowadays[3].

The magnetical azimuth resulted to be 260°.

Near winter solstice

(data of

The magnetical azimuth was measured in 225°. Unfortunately, as

the time of sunset wasn’t recorded we couldn’t measure the astronomical

azimuth.

|

Picture 5: The

winter solstitial sunset (photo by |

Near summer

solstice (data of

The magnetical azimuth resulted to be 289°.

|

Picture 6: The

summer solstitial sunset (photo by |

The range between

the point of equinoctial sunset and the point of summer solstitial sunset was

measured by means of our graduated spherical surveyor’s cross in 29°, while the

range resulting from the difference between the astronomical azimuths was 26.5°.

We can therefore

draw that the average range is 27,75°, with a standard deviation of ± 1,25°

nowadays.

It results that solstitial

setting amplitudes in winter and in summer (that is the two horizon arcs between

the equinoctial, winter and summer solstitial sunset points), are 34,5° and

27,75° nowadays, while the total arc, which shows the annual local apparent

range of the Sun, is 62,25° (the magnetical arc is

64°).

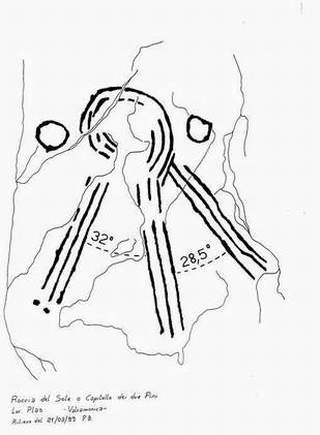

This is also what

you can draw from the engraving which we are examining: the two angles between

the central beam of rays, the one on the left and the other on the right

(looking at the engraving) are, respectively, 32° and 28,5°, while the total

angle is 60,5°.

We think that these

data ratify our first hypothesis: the Sun’s

(Camunian) Engraving reproduces, as stylized

shape but with the quite same angular distance, the three basic sunset points

(of equinoxes and of summer and winter solstices) on the local skyline.

Small rings close

to the big one could represent: 1. Sun position during equinox and solstices;

2. Sun position at sunrise, midday and sunset; 3. Moon extreme positions at

sunset, reached every 18,61 years, when orthiva and occasa[4]

amplitudes are broader than Sun amplitudes during solstices. In these

situations, we think that they represent the option No 3rd, i.e. the

Moon to rise and set southern and northern than the Sunsets during winter and

summer solstices.

Options 1 and 2

don’t look likely, because option 1 has already been represented by the light

behind the rings, while option 2 is difficult, because of the morphology of the

land, with a bad vision during sunrise. So we think that option 3 is the one

pictured on Plas’ rock. Also considering that Moon

extreme positions were the most observed during megalithism in

As a further proof

of our interpretation, on

We also watched a

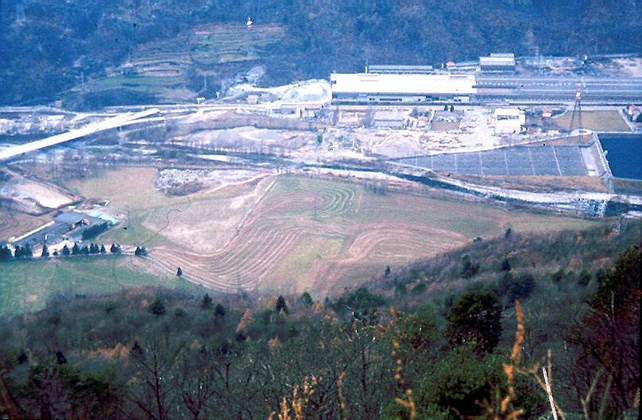

field (picture 7), at the bottom of the valley, ploughed in a horseshoe way (Brunod 1997, picture n. 5). That made us think that similar

engravings- Caven 3, Cornal,

Borno 1, Ossimo 2- could represent

the whole land-sky environment (see Brunod, 1997,

pictures 74-75).

|

Picture 7: The field

ploughed in a horseshoe way from Plas (photo by |

Before the book of Brunod, Cinquetti, Pia and Veneziano printed in

2008, we thought that reproducing the different range of sunset amplitudes of

wintry and summery solstice could have been realized using four wooden posts,

one of them intended as an observation point and the other three posted where

the three sunsets fallen. Using a rope, it was possible to take measurings of

the amplitudes, and reducing the whole structure it was possible to obtain a

“circular field”, where the proportions were the same. In this way, the rope

was a measuring unit for the engraving. We can remember that similar, but more

complex, explanations, have been proposed by A. Thom about the megalitical alignments in Britain and Scotland (Thom, 1971;

Hadingham, 1978; Proverbio, 1989; Cossard,

1993) and by C. A. Newham about Causeway Post Holes in Stonehenge (Hadingham, 1978; Proverbio, 1989). Despite the experts

don’t accept anymore the idea of “megalithical yard”,

proposed by

But nowadays we

agree with the hypothesis of Brunod et Alii (Brunod, Cinquetti,

Pia and Veneziano 2008) that

the ancient engravers used – like a gnomon – the shadow of a wooden (or by some

other material) stick leaned against the centre of the main ring and against the

ground with an inclination of 45°. Brunod, Cinquetti, Pia and Veneziano showed that in these conditions the shadow of the

“gnomon” is superimposed to the central beam of rays at the equinoxes and it

touches the internal one of each beam of rays at the solstices. This is the

simplest and the most careful method to engrave this figure! Thanks to this

idea, our hypothesis that the Sun’s (Camunian) Engraving is a portrayal and a stylization of

the sunset in its four main annual times – i.e. the equinoxes and the solstices

– becomes probable and a probability can be calculated: it would be interesting

to calculate how much it is probable that the angular range of the three beams

of rays coincide randomly with the angular range of the three equinoctial and solstitial

Sunset points on the visible skyline. But we do not agree with the hypothesis

of Brunod, Cinquetti, Pia and Veneziano that the

engravers’ aim was to build a sundial measuring not daily-time but seasonal-time.

In their book 2008, the four authors write that the engravers could use the

movement of the stik’s shadow to know the dates of

equinoxes and solstices: but why to use this strange kind of sundial instead of

to look at the sunset positions on the skyline? The skyline in front of Plas is the best yearly sundial and seasonal calendar because

it allows to determine and to count each day of a year much more carefully by

means of the shifting of the sun-setting position from one solstice to the

other. Therefore, we think that the Sun’s

(Camunian) Engraving is not a yearly sundial,

although it was built using the gnomon shadow, but a stylized symbol

(religious?) of the Sun.

Someone objected

that the Sun’s (Camunian)

Engraving is a jewel or a neck-lace, especially of a Goddess. In our view this is not

in contrast with the precise astronomical significance as we proposed here. In

fact, as is known, according to the orthodox Freudian psychoanalysis, the

original symbolic representation of an "object" or of a pregnant

event undergoes with time a separation from '"object" and its

portrayal, it gets an autonomous development and, at the end, the meaning

original symbol is completely forgotten or "repressed" while the

symbol acquires its apparently independence. Therefore, the original

relationship with the '"mother object" is recognizable only analytically

(Freud, 1900;

In our case, although in

the presence of a very pregnant less motivation drive, we can assume a similar

mechanism: forgotten with the passage of time and generations its original

astronomical and religious[7]

significance, the Sun’s (Camunian) Engraving could have turned into a mere

ornament, thus losing the immediate contact with the event (astronomical) that

had generated. A similar fate might have had the swastika from its original meaning

(heavenly probably) to its spread as a simple ornamental figure (on vases,

etc.)[8].

Therefore, we do not

reject the explanation of the Sun’s (Camunian) Engraving as a jewel or a neck-lace,

but we assert that firstly this engraving was probably a stylization of an

astronomical and religious phenomenon (i.e. the yearly shift of the sun-setting

point on the local skyline) and that it became a jewel or a neck-lace

afterwards and as a result of its religious meaning, just like the cross in

Christianity.

During our surveys,

Adriano Gaspani studied as the same engraving as some others, which can suggest

astronomical interpretation (Gaspani 2000, pp. 32-39). He suggest that it

symbolizes a three-tails-comet between two stars. He names also two other

interpretations: a solar eclipse and a three-planets-conjunction. As the same

engraving is reproduced in other rocks (he mentions ten of them), also far from

Plas place, he suggest that it symbolizes an

extraordinary event “…really watched in the sky by far peoples with different

cultures…”. We think these are weak interpretations, because they are founded

only on a morphological likeness of a not just demonstrated but only guessing

heavenly event. Really the presence of the same – or, better, alike - engraving

in far cultural areas[9][10]

put some questions and force to regard it as the representation of an important

and diffused “thing” (like, for instance: the calcolithic

dagger with triangular blade, central rib and half-Moon shaped pommel; the

tongue shaped axe; the metal double spiral; the pintaderas;

etc.). But we think that the collected (by us and by Brunod,

Cinquetti, Pia and Veneziano) and up-discussed data back up more strongly the hypothesis

that it symbolizes the sunset, which was much watched during the Metal Age,

like the European and Mediterranean megalithic monuments show. If a surveys in

these other places would show similar bearings towards the sunset (or the sun-rising)

and similar correspondences between engraving angles and Sun movements on

skyline, this hypothesis would be strengthened. Unluckily some of the more

important menhirs with the alike engraving (as, for instance, Caven) were removed and it’s not possible to restore their

exact position any longer. People who will decide a this kind survey in the

future, will be obliged to get their data only from irremovable engravings.

The question of equinoxes: wilful or

random?

During the archaeoastronomical

international meeting Archaeoastronomy: a

debate between archaeologists and astronomers looking for a mutual method

taken place in Genoa (Italy) on 08-09 February and in Sanremo (Italy) on 01-

A first method is

to recognise, by means of a Polar Star (if there is in that time), the

direction N-S, which is the polar axis: its orthogonal line is the direction

E-W.

To recognise the

North or South Pole in absence of a Polar Star can be made in the following

ways:

a) watching the starry sky very carefully during a

large number of nights: a diligent observer can locate the point around which

the starry sky turns;

b) looking the rising and setting of a circumpolar star

through an horizontal plane: as the circumpolar star describes a ring in the

sky, the central point between the two extremes of the half ring is the sky

pole (Romano 1992 pp.186-189).

c) Looking at the highest height of the Sun, which

coincides in the transit over the local meridian with enough approximation.

All these methods are simple, intuitive and within a diligent observer’s

grasp.

A fourth method is to use the gnomon put upright in the middle of some

horizontal and concentric circumferences, whose points, touched the first in

the morning and the last in the afternoon by its shade, lie on the axis E-W

(Romano 1992 pp. 37-38, 186-189).

It needs more knowledge than the first three methods, but it seems to be

very ancient.

A fifth method is to calculate the mean time between two solstice: it is

not exact because the not uniform speed of the Earth around the Sun (Romano

1992, 38-39; Proverbio 1989 pp. 190-194), but the mistake totals few days only.

According to A. Thom a prehistoric

calendar was got dividing in two the distance between the solstitial sun-rising

or sun-setting points; than dividing in two each one of these halves and

repeating this division till they got sixteen partitions, i.e. sixteen

directions, i.e. sixteen months (Proverbio 1989, pp. 190 – 194). More probably

the undeniable megalithic alignments E-W were made using a mixture of all methods:

there are few doubts that old calendars began since the spring (or, less often

the autumnal) equinox. See for instance the fragment 4Q318 from Qumran (Eisenman and Wise 2006,

pp. 258 – 263; Codebò submitted) and the MUL.APIN (Hunger and Pingree 1989, pp. 153 – 154).

It is important that the archaeoastronomers do not mistake the astronomical

equinox (which is not obvious) for the E-W alignment (which is easily building).

We think that it would be useful the experimental archaeoastronomy, in order to

test what prehistoric peoples could really see and understand about heavenly

motions by the means they had.

Conclusions and synthesis

Plas was an exceptional “emplacement” of territory’s control for a wide

beam, guaranteeing not only a visual dominion on fields, pastures and ways of

communication, but also a place for the Copper Aged religious cult of Sun and

visual width on local skyline, on which it was possible to follow the path of

the sun-setting from the winter solstice to the summer solstice and back. The

angular distance between the sun-setting points of solstices and of equinoxes

is quite the same between the three rays bundles of the Sun’s (Camunian) Engraving, which we can

therefore interpret as a stylized portrayal of Sun’s yearly movements. The two

side minor circles may stand for the extreme Moon’s standstills. The engravers

used probably the shadow of a gnomon to engrave it. This engraving became a

“symbol” of the Sun religion and was exported elsewhere. First the Romanization

and than Christianity caused the oblivion of its original astronomical meaning

and this symbol – and many others – became incomprehensible. To understand

prehistoric symbols and civilization we must recover their explanatory keys (

Acknowledgements

We must thank the

other authors of our first survey

Bibliographical references

Barale Piero (submitted) La pietra del Sole. Un antico “sasso”

astronomico dall’augusta Bagiennorum, Proceedings of the

International Meeting “Representation d’astres,

d’amas stellaire et de constellations dans

Beretta Claudio

(1997). Toponomastica in Valcamonica e

Lombardia. Edizioni del Centro, Capo di Ponte (BS), Italy.

Brunod Giuseppe (1997). Massi

incisi in Valcamonica. Associazione Cristoforo Beggiani

ed., Savigliano (CN), Italy.

Brunod G., Cinquetti M., Pia A.,

Veneziano G. (2008) Un antico

osservatorio astronomico, Print Broker, Brescia, Italy.

Brunod G., Cinquetti M., Pia A.,

Veneziano G. (2012) Un antico

osservatorio astronomico – Valcamonica, Brescia, Paspardo.

Burl

Burl

Burl

Codebò Mario, Michelini

Manuela (

Codebò Mario (1997b). Problemi

generali dell’indagine archeoastronomica. In: Atti del I seminario ligure

di archeoastronomia. A.L.S.S.A. e Osservatorio Astronomico di Genova, Genova, Italy.

Codebò

Codebò M., Barale G., Castelli M., De Santis

H., Fratti L., Gervasoni E.

(1999) An Archaeoastronomical

investigation about a Valcamonica’s engraving near

the Capitello dei Due Pini, Pre-Tirages of 17th Valcamonica Symposium, Darfo

- Boario Terme (BS), Italy.

Codebò M., Barale G., Castelli M., De Santis H., Fratti L., Gervasoni E. (2004) Indagine

archeoastronomica su un petroglifo della Val Camonica presso il Capitello dei

due Pini, BCSP, 34, Capo di Ponte (BS), Italy.

Codebò M., Barale

G., Castelli M., De Santis H., Fratti L., Gervasoni

E. (2005) La roccia camuna del Sole:

un’ipotesi archeoastronomica, Quaderni del L.A.S.A., 2, Zuccarello (SV), Italy.

Cossard G., Mezzena F., Romano G. (1991). Il significato astronomico del sito

megalitico di Saint Martin de Corléans ad Aosta. Tecnimage

Edizioni, Aosta, Italy.

Cossard Guido (1993). Le

pietre e il cielo. Veco editore, Cernobbio (CO), Italy.

De Santillana G., von Dechend H. (2004)

Il mulino di Amleto, Adelphi, Milano,

Italy.

Eisenman R.H., Wise M. (2006) Manoscritti segreti di Qumran,

Piemme Pocket, Casale Monferrato (Alessandria), Italy.

Flora Ferdinando

(1987). Astronomia Nautica. Hoepli,

Milano, Italy.

Freud Sigmund (1900)

L’interpretazione dei sogni. O.S.F.

vol. 3rd, Boringhi, Torino, Italy, 1980; o.t.: Die Traumdeutung,

G.W. 2-3, S.E. 4-5.

Freud Sigmund

(1915-1917). Introduzione alla

psicoanalisi. Lezione X. O.S.F. vol. 8th ,

Boringhieri, Torino, Italy,

1976; o.t.: Vorlesungen zur

Einführung in die Psychoanalyse,

G.W. 11, S.E. 16.

Fromm Erich (1982) Il linguaggio dimenticato, Bompiani

tascabili, Milano, Italy.

Gervasoni Elena (1997). Per

un’archeoastronomia rupestre in Val Camonica. In: Atti del Valcamonica

Symposium ‘97, Capo di Ponte (BS), Italy.

Hadingham Evan (1978). I misteri dell’antica Britannia.

Hinshelwood R.D. (1990) Dizionario

di psicoanalisi kleiniana, Raffaello Cortina, Milano, Italy.

Hunger H., Pingree D. (1989)

MUL.APIN An Astronomical Compendium in

Cuneiform, Archiv für Orientforschung, Verlag F. Berger

& S. Gesellshaft M.B.H., 24,

Laplance J., Pontalis J.B. (1990) Enciclopedia della psicoanalisi,

Laterza, Bari, Italy.

Mezzena Franco

(1997).

Musatti C.L. (1977) Trattato di psicoanalisi, Boringhieri,

Torino, Italy.

Priuli Ausilio (1983). Incisioni rupestri nelle Alpi. Priuli & Verlucca, Ivrea (TO),

Italy.

Proverbio Edoardo (1989). Archeoastronomia. Nicola Teti editore,

Milano, Italy.

Rycroft C. (1970) Dizionario critico di psicoanalisi, Astrolabio, Roma, Italy.

Smart W.M. (1977). Textbook on spherical astronomy.

Veneziano Giuseppe

(2009) Le antiche conoscenze celesti come

strumento di potere sociale: il possibile caso della Rroccia

del Sole a Paspardo, 11th A.L.S.S.A.

Workshop, Genova, Italy.

Zagar Francesco (1948). Astronomia

sferica e teorica. Zanichelli, Bologna, Italy.